Chocholow Uprising Museum, Chochołów

Opened in 1978, the Chochołowski Uprising Museum is housed in a historic cottage that once belonged to a wealthy smallholder by the name of Jan Bafia. The cottage was built of wood in a style typical of the Podhale region. It has an entryway, a room known as a ‘black chamber’, another known as a ‘white chamber; and, above that, a space called a wyżka. This was a chamber located in the attic in the rural and small-town dwelling places of bygone times. They can still be found today in Podhale and the Orawa region. The interior has been arranged in a way that combines the history of the Chochołów Uprising … which is important to the region … and an ethnographic exhibition which gives visitors an insight into how a family of highlanders would have lived in the mid nineteenth century.

The Podhale village of Chochołów has a rich history stretching back to the early sixteenth century. What won the village the greatest fame in Podhale was the Chochołów Uprising of 1846 … a short-lived, armed revolt against the Austro-Hungarian authorities which occurred at the time of the Krakow Rebellion and preceded the Springtime of the Peoples by two years. The plan to join the uprising against the Austro-Hungarian monarchy was born of contact between emissaries who reached Podhale and local conspirators who made contact with national activists.

They were … the teacher and organist, Jan Kanty Andrusikiewicz … the priest from Chochołów, Leopold Kmietowicz … and the priest from Poronin, Michał Głowacki, known as Światopełk. Later on, they would stand at the forefront of what became known as the Chochołów ‘agitation’. The exhibition presents the preparation and course of the Kraków revolution in 1846, and the Chochołów uprising the following year. The museum offers an insight into the people who led the uprising and provides the chance of seeing documents relating to the armed revolt and a list of those who took part in it. Visitors can also explore the mournful topic of the sad end to the ‘agitations’ … in other words, the repressions carried out by the Austro-Hungarians, one of the three powers which had divided Poland between them at the end of the eighteenth century and wiped that former sovereign state from the map of Europe.

The Chochołów Uprising may have been brief, but it lived on … and still lives on … in the minds of the villagers. This is confirmed by documentation on display in the museum which records the ceremonies marking the anniversary of the Uprising, particularly on the threshold of the struggle for independence in 1913. The exhibition is rounded off by a display of literature … scientific, poetry and prose …where the Chochołów Uprising is reflected. There is also a collection of contemporary folk art which takes the insurgency as its theme and addresses it in sculpture and paintings on glass.

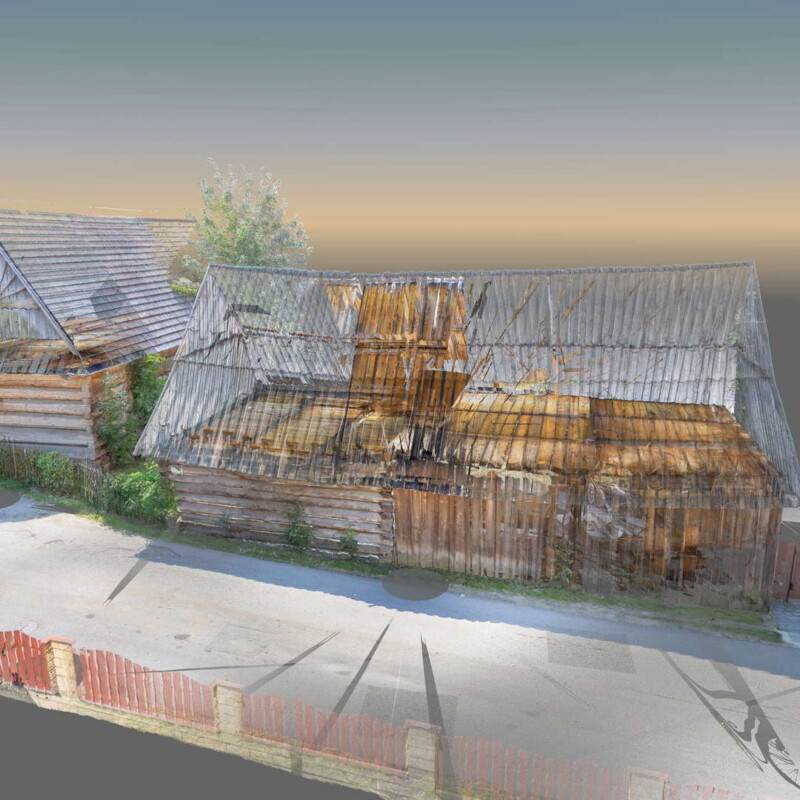

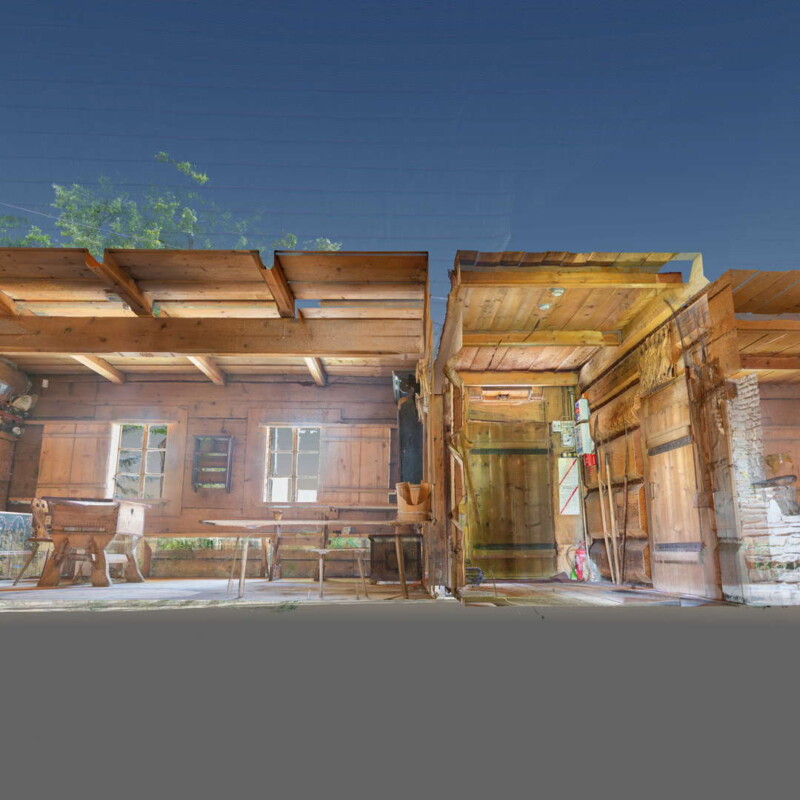

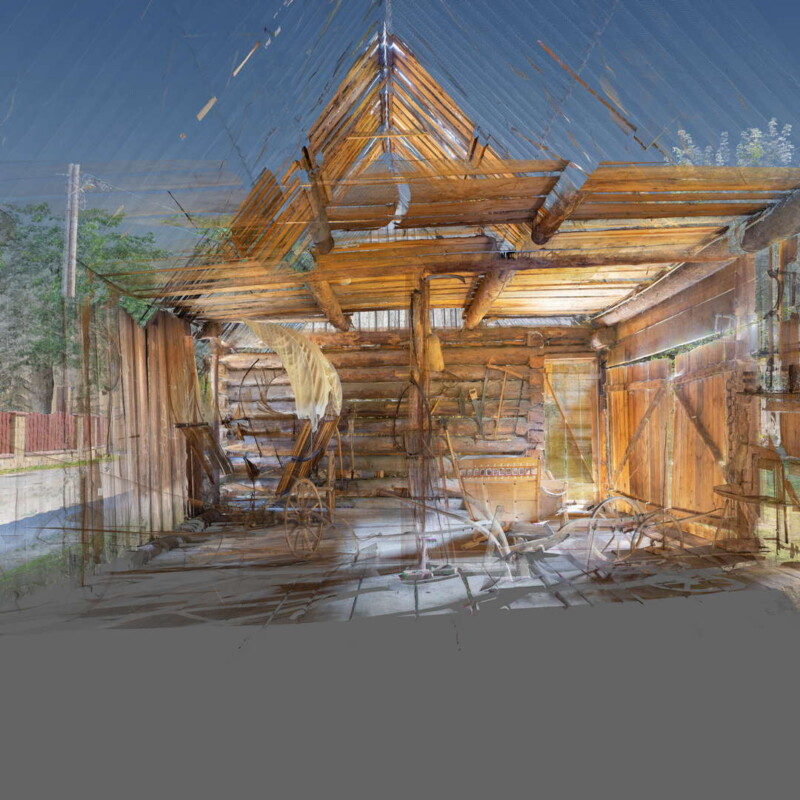

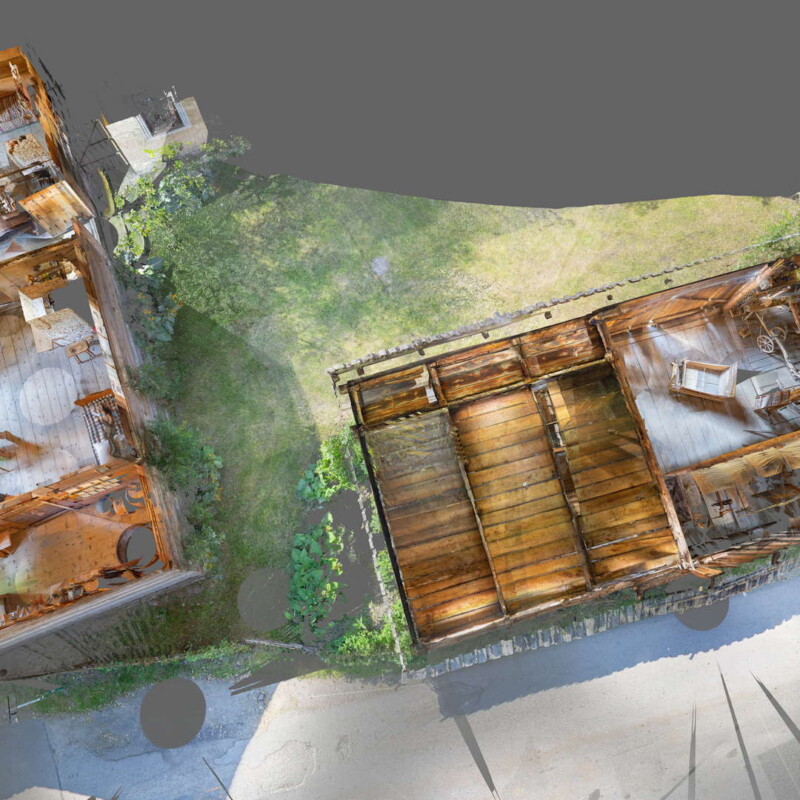

Application – a virtual walk around the object

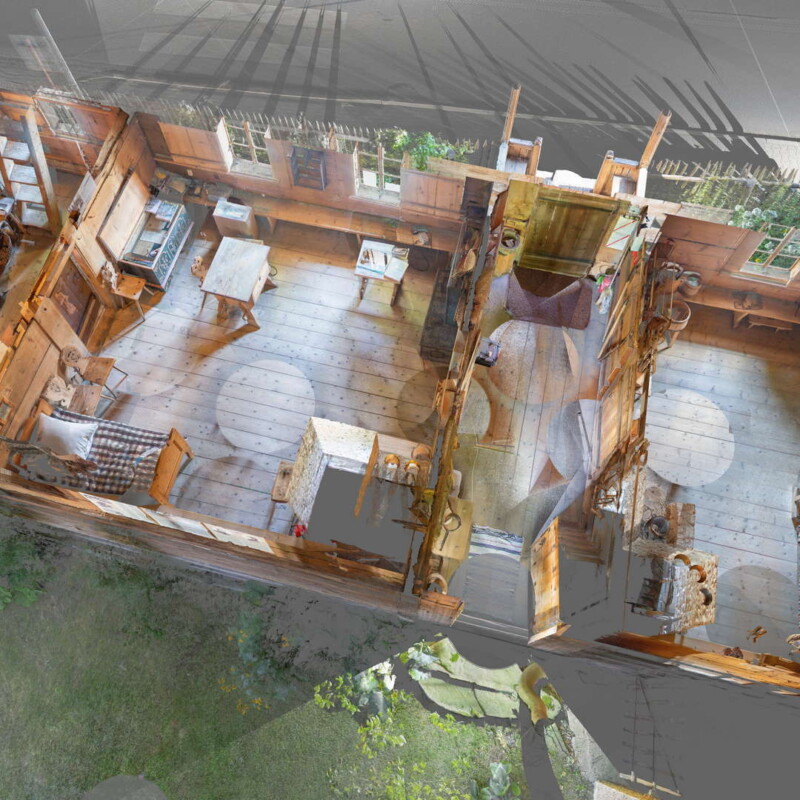

The cottage that houses the museum is wooden. It was built to a rectangular plan. The walls were constructed using thick beams, laid horizontally. The steeply sloping roof is clad in shingles … in other words, small, thin, tapering pieces of wood that are laid out to overlap one another. Inside, there are several separate spaces … an entryway, a room known as a ‘black chamber’, another known as a ‘white chamber; and, above that, a space called a wyżka … a chamber located in the attic. The white chamber is around seven metres long and four metres wide. The floor, ceiling and walls of the white room are clad with planks of a wood and, beneath the ceiling, wooden cross-beam run from wall to wall.

A thick wooden beam is set at a right angle to them and parallel to the long wall. It’s known as a sosrąb … a word that derives from sosna … which translates as ‘pine tree’. On one side, it runs up to the door leading into the white chamber and, on the other side, it meets up with the door leading into the next, smaller room. The beam is engraved with decorative patterns and inscriptions, including the letters ‘I’, ‘H’ and ‘S’. To the left of the door to the white chamber, there’s a white stove built using flat, whitewashed stones. It’s almost cuboid in shape. To the right of the stove, a shelf hanging on the wall above a dark wooden chest holds various items of crockery. A vessel of holy water has been mounted on the left-hand side of the door frame.

Above the door, leading to the smaller room, there’s a long strip of wood running up to the sosrąb beam at a right angle. Traditional paintings on glass have been hung behind it at an oblique angle to the wall. The paintings portray colourful images of saints. The strip of wood is also equipped with hooks. There are clay jugs painted with floral motifs hanging from them. To the left of the door to the smaller room, there’s a bed covered with a brown-and-white blanket and ornamental cushions. To the right of the bed, there’s a large, painted wooden chest, which is more than a metre high. Beside that, there’s a wooden table. Long planks of wood nailed to the longer walls of the room form benches. To the left of the door, there are information boards telling the story of the uprising.

The smaller room is a square. It’s around four metres by four. To the right of the door, there’s another stove made of flat, whitewashed stones. This one is an irregular polygon in shape. The highest part of the stove measures around two metres, while the lower part, closer to the door, is just over over a metre high. A selection of cooking pots sits atop the stove. Inside the room there’s a cradle with a bed to it. The bed is covered with a black-and-white bedspread and has two pillows, one on top of the other. By the wall, there’s a spinning wheel. Along the wall between the stove and the bed, there’s a long bench made of a single board of wood. The walls are hung with illustrations set behind glass. They present the history of the area, its people and their culture.